When I learned David Berman died in 2019, I was sitting at a table in some very bland Italian place near Union Square and the first thing that popped into my head was the song "Death of an Heir of Sorrows” from his 2001 Silver Jews album Bright Flights.

When I was summoned to the phone

I knew in my bones that you had died alone

We'd never been promised there will be a tomorrow

So let's just call it the death of an heir of sorrows

The death of an heir of sorrows

I remember the next few days very clearly, mostly because after the bland Italian restaurant I had to go to a garage in Chelsea to pick up a Corvette that I was supposed to drive, strangely enough, into Berman’s home state of Virginia the next day. When I got to the garage I was told there was a problem delivering the Corvette and they gave me a Camaro instead.

That’s fine. Corvette or Camaro, I was still going to do what the good lord intended in a fast American car and blast some music as I cruised the highway. Except instead of Bon Jovi or Warrant, I blasted "Death of an Heir of Sorrows.”

Rock and roll, baby.

The thing is, “Death of an Heir of Sorrows” was about an actual person. The lyrics felt eerily fortuitous about his own death at the time given what we knew about Berman’s life and what we’d learn about his death, but he had written the song about his friend, the writer Robert Bingham, who died of a heroin overdose at the age of 33 just a few years earlier in 1999.

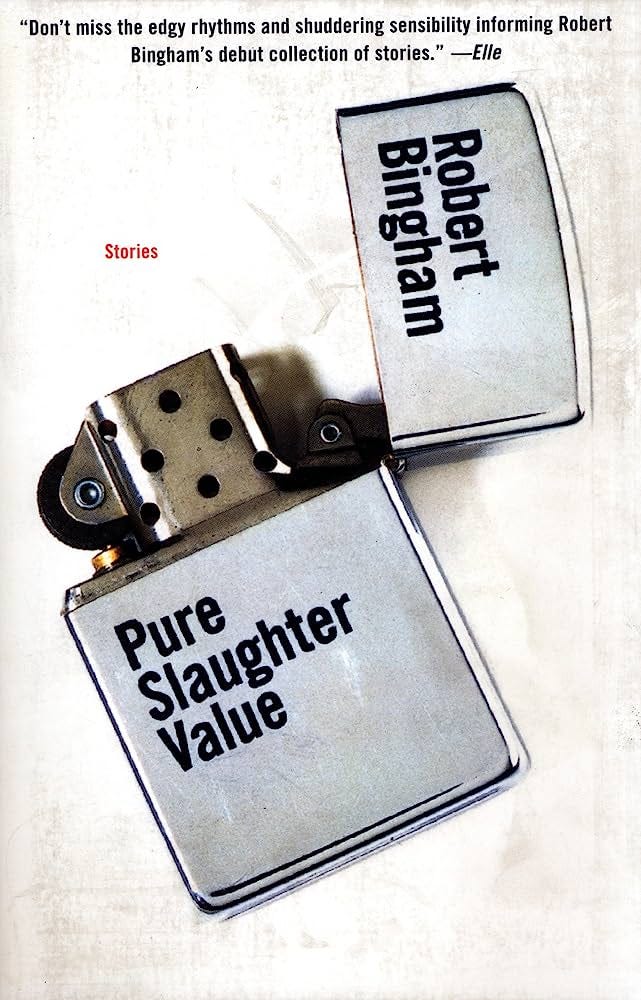

I’d first read Bingham’s 1997 short story collection, Pure Slaughter Value, when I was about 19. He had a novel released posthumously a year after his death, Lightning on the Sun, but it’s the stories I’ve kept on my shelf for the last few decades. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Bingham was one of the best modern examples of a person who came from wealth writing about troubled wealthy people. I find that when done well, this is one of my favorite types of fiction. It would explain why I was drawn to Bret Easton Ellis pretty early on, why. I eventually gravitated toward Edith Wharton, and why I consider Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose books some of the best novels I’ve read. And, maybe not coincidentally, it just so happens that the publisher that first put out St. Aubyn’s books, Open City, was originally a literary journal that Bingham helped to start.

Bingham’s story is out there. A novel could be based on it. Coming from the family known as “the Kennedys of Kentucky,” both for their wealth but also for the tragedy that seemed to follow them around. From a 2001 Guardian article:

Bingham was three months old in 1967 when his father, Worth Bingham, a drinker and womaniser, was killed driving his family to the beach. Bingham and his four-year-old sister Clara watched as the tip of a clumsily packed surfboard, slung across the back seat and protruding from the window, clipped a parked car, swung round and crushed their father's neck against the windscreen.

It was neither the beginning nor the end of the Bingham family's tragedies. Worth's mother had been killed in a car crash and his stepmother died a few months after marrying his father, who was rumoured to be guilty of her murder. Two years before Worth's death, his eldest brother, John, was electrocuted stringing up fairy lights for a party. Then in 1995, Robert's grandmother Mary received an award for philanthropy in Louisville and died just moments after saying that 'the best thing would be for a big pink cloud to come down and take me away'.

There’s a lot of darkness there, and it found its way into his fiction. I recently picked the collection back up because I’d been thinking about it after the series finale of Succession left me thinking about the idea of emptiness. The characters in Bingham’s stories, like the Roy clan, have everything they could ever want, but they’ve got nothing inside. They’re so rich that they’re numb. That is an ongoing theme in American art over the last century or so, whether it’s Gatsby or Citizen Kane, but I think there’s something extra added to it when the person creating the art actually comes from that world. Fitzgerald was born middle-class, but was around and obsessed with wealthy people, while Welles was born into an affluent family in Kenosha, Wisconsin, but knew plenty of hardship growing up. That’s not to say somebody like Bingham didn’t know hardship, but I don’t think he ever lived in fear of not having all the money and privilege just vanish. And that’s what makes fiction like his so interesting to me. All the people in his stories, whether they’re cheating husbands or a banker willing to risk it all for the love of a drug addict, every story Bingham writes leaves me feeling like I just looked into a great pit. There’s nothing left besides sins of the flesh, and his characters usually find that committing those can actually lower you even further than they’d thought possible.

I think a lot about the connection between reading fiction and empathy. I read a lot of fiction, but I like to think that I’m very purposeful with what books I choose to spend my time with. I try to get fiction from plenty of different viewpoints, different voices, cultures, and countries, and I think if I can say I’m a decent person, part of it is because of how much I read. But fiction like Bingham’s—and to a certain extent, stuff by Ellis. or St. Aubyn fills a similar role—does something else for me. It makes me grateful. I really like fiction about rich people and their problems when it’s done by somebody who truly understands that world because it’s as close to the void as I’m comfortable with. It tests my empathy because, yes, a lot of these characters do terrible things and I’m forced to hold out a little hope that there’s redemption. But there often isn’t, and that’s OK. In a lot of ways, sad rich people writing about sad rich people is the perfect kind of American (and, in St. Aubyn’s case, British) morality tale. The best ones are reminders that nothing is ever close to perfect, and the things we might think of as dreams might actually be nightmares.

I was interested to read Pure Slaughter Value after reading your article, it’s practically impossible to get hold of here in the UK.

Rob was a classmate of mine in the MFA program at Columbia and would workshop parts of what became PURE SLAUGHTER VALUE. He was always nice to me but I couldn’t help but be intimidated by him.