I’ve been thinking recently about doing a book club. I write about a book every month or so over here, and I think there’s a very deep flaw in the way we discuss literature in America, how books are tied to the same news cycle as movies or albums. Say a novel or essay collection comes out on Tuesday, there’s usually a very short window most (not all…) publications will write about it. Maybe two or three weeks. And in some ways, I get that. You want to capitalize, especially given the way we filter through the news so quickly. But there’s also so much out there, and books aren’t as easy to digest as two or three episodes of a television show or Oppenheimer. The new Christopher Nolan is 180 minutes long. Most people would get through maybe half of a 300-page book in that time, and that’s if there are no distractions. I’d love to try in some small way to be able to give some books a little more room to grow, because that short window really doesn’t do much given the investment of time readers have to be willing to give up. And for some books, the window doesn’t even open.

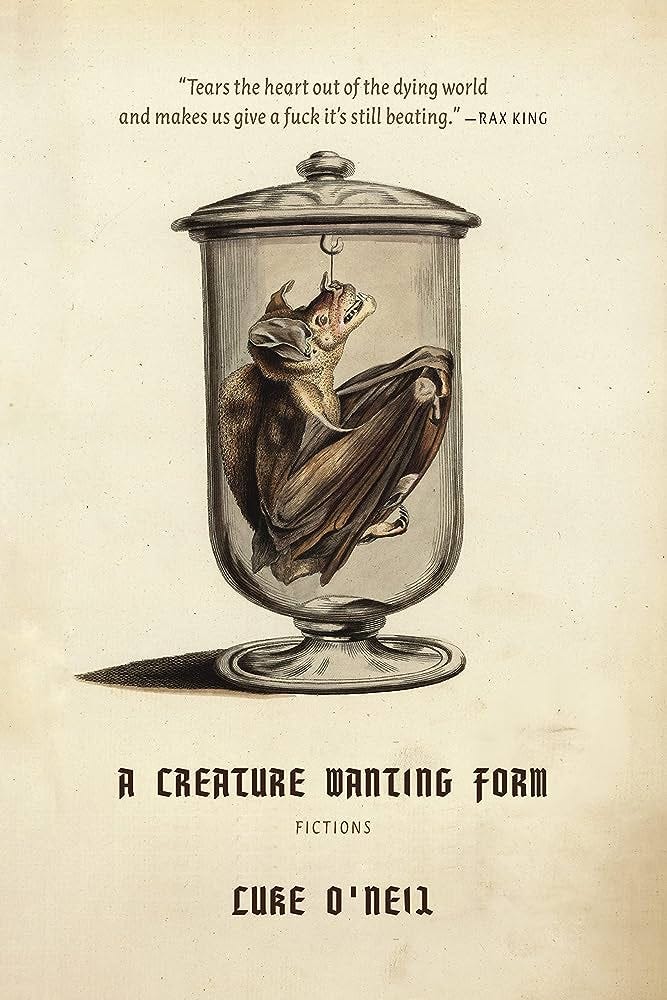

Luke O’Neil’s A Creature Wanting Form, got me thinking about this again. This is no commentary on O’Neil’s writing, which I’m a very big fan of, but it’s not exactly the sort of book I see the Times or New York Review of Books giving up a page or two for. Part of that is because it’s on a smaller press, and small presses and the books they publish, as vital as they are to a thriving literary culture, still don’t get the coverage they need to reach a wider audience. I put out my last book on one. A very respected and older indie publisher that I love, and watching the way they did things with hardly any team or budget was inspiring.

O’Neil’s book is also strange. I say that with all the respect in the world. I mention my longstanding fandom reading his “Welcome to Hell World,” one of the first newsletters that ever became a regular part of my media diet or whatever the hell you call reading stuff online all day. You get unflinching honesty when you read O’Neil’s stuff. The world is dark and full of terrifying people with horrible intentions, and O’Neil has made a place for himself by exploring all that in a way that’s engaging but also doesn’t make the reader feel like a dummy. Part of it is O’Neil is removed far from the media world of NYC or the Beltway drama of D.C. (well, he’s in Boston, so maybe not that far in terms of mileage) but I also think it’s because he’s got that punk/DIY training, so instead of feeling like you’re reading something handed down from a skyscraper in the middle of a big city, it’s more like being at a basement show and the band is telling you to crowd closer to them. There’s an intimacy about it, and the real emotion that comes through. O’Neil is a writer, journalist, commentator, editor, publisher, or whatever he wants to call himself. But he’s also a human, and the things he’s writing about, I have to believe, trouble him deeply.

That’s what interested me about his book of fiction. It’s not a novel. O’Neil can write as somebody else if he so wishes using that form. I suppose you could say it’s short stories or vignettes, but I don’t want to mislead anybody with labels. Some of the stories take up a quarter of a page, while some of the stuff could be filed under poetry or allegories. One, for instance, “To the Ground,” is a meditation on an ant crawling across a porch that ends with the line “When it’s expected of you to work yourself to death maybe exhaustion isn’t even a concept.” It’s a neat little trick he pulls in maybe 200 words or so, putting us in the shoes of somebody watching an ant, something we can literally walk outside right now and probably do, then giving it deeper meaning. The lesson is that there can be something taken from anything. The world is terrifying, but it’s also filled with wonders and lessons. The problem is humans take those wonders for granted, and we’re actively doing all we can to ruin what we’ve been given.

Maybe it’s stark, but that’s life. It’s also a glimpse into O’Neil’s brain we maybe don’t get reading his newsletter. Tales in his book start with people driving north and east to coastal Massachusetts to look at an old pink house, and it sort of descends into terror with a guy floating in the water, unable to get images of stuff he saw online, war, and violence. I don’t know if the story is “about” that, but as a reader, I felt particularly freaked by the idea that even in nature, all the media we tell ourselves that we consume, all the stuff we watch, and read, all the tweets (or whatever we’re calling it on X now) or TikToks, is actually consuming us.

I’m not trying to write a book review here. There’s too much in this book and I’ve already written too much. Rather, I’m hoping more people will read a book like O’Neil’s because I think it offers something far different than you’re likely to find at an airport bookstore. I also think O’Neil is onto something interesting that calls to mind the sort of writing that was popular during the Nixon years, then sort of died away and was reborn as myth. We’ve beaten to death the idea of New Journalism and some of the writers associated with it have been lionized maybe a little too much, but I certainly wouldn’t be here writing this if I didn’t read Tom Wolfe or Joan Didion at an impressionable age. And, yes, I still go back to a few of them from time to time. But I am always fascinated with the idea that there was a time just a few decades ago when editors like Clay Felker were just like “You know what, let’s send Norman Mailer to the 1960 Democratic convention and see what happens,” and magazines like Esquire or The New Yorker would give the green light. Some pieces associated with New Journalism aren’t so good. Sorry. And more than a few of the articles I do love could be 1,000-5,000 words shorter. But that’s not the point, and O’Neil’s work doesn’t really mimic any of the writers associated with the style. But there is a spirit there that I only really started to understand reading his fiction.

One of my favorite things about New Journalism was the blurring of lines between fact and fiction. Some people hated that, they thought it deviated from the truth. And maybe it did. I won’t argue if somebody wants to say Wolfe or Hunter S. Thompson did too much writing (and drug taking) and not enough reporting, but I also don’t care. O’Neil, with his fiction, sort of does the reverse. He’s known for his journalism, but his stories feel very real. They read like experiences, things seen through his eyes. Maybe he distorts the reality in hopes of making some mundane moment more powerful or readable, but it only benefits the reader. O’Neil is doing something different. It’s weird. Likely some person with a business degree could tell you why his book won’t sell a million copies, and maybe they’re right. That’s a shame, of course. But the unfortunate truth is some things take time to catch on, especially when it comes to writing. O’Neil has been a favorite writer of mine for some time. I lump him in with writers like Hanif Abdurraqib, David Roth, or Lyz Lenz. Again, not in terms of style, but where they came from, what they tell us about America, and the way they tell us. Abdurraqib is a poet first, many of us became familiar with Roth through his sportswriting, and Lenz has established herself as a strong voice in the American conversation from as far away from any centers of media as possible. They’ve all built their audiences in a very grassroots way and they’re part of a small group of writers I think are all doing something unique and interesting, largely through independent outlets or publishers. And with his book of fiction that feels very real, O’Neil has given me another reason to say things are really bad, but there’s something really interesting happening in American writing if you just scratch the surface a little.

Jason!!! This is so nice. What awe inspiring company to toss me into.

down for a book club!