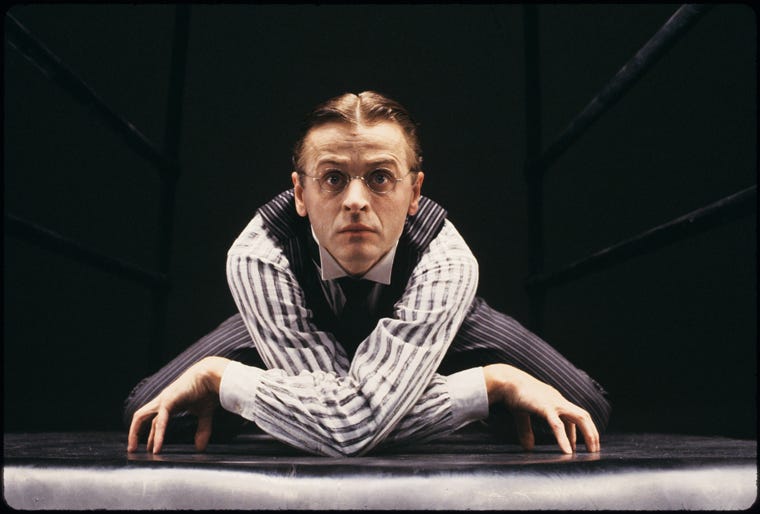

I started working on a profile of Mikhail Baryshnikov for the New York Times Magazine two weeks before my wife got pregnant. My baby turned seven months last week, so you do the math and figure out how long it took for the thing to see the light of day (online today, in print this weekend) for an idea of how long these things can sometimes take. Some writers famously love to take as long as humanly possible to work on things, but coming up through the rank and file of the blogging world, room to truly work on something is still something I’m not accustomed to. Frankly, having over a decade of experience cranking out 3,000-word pieces on a 24-hour deadline means that having the time to write actually freaks me out a little. I noticed it as I was writing my novel last year, that grave feeling that if I didn’t finish the book fast enough…it would be too late. Maybe somebody else would have the same exact idea as me and they’d get their piece up faster, meaning my piece would either die a death that only I’d mourn, or worse: the piece would publish and it would look as if I was copying the writer who’d beaten me to the punch.

I believe that is a very specific 21st-century writer problem. Sure, journalists have always had to compete for “scoops” and you can find plenty of stories of critics holding onto their reviews until the last second so they could change things up at the last second so they didn’t echo their competition, but starting out writing mostly “for the internet” meant I was hardened to get my take or review or whatever up as fast as possible. It taught me to be a more precise writer, as well as a somewhat decent editor as well. But it also made me question what the hell I was doing since I wanted to be a writer and not some Canaanite throwing their baby down the throat of Moloch the God of Content. And that was in the mind while writing the Baryshnikov piece. It’s about the artist and his third act—turning 75 and trying to make sure his legacy is intact—but it’s also about art in America and what we do and don’t value anymore. My hope was that by showing how I don’t see there being somebody in the current cultural conversation like Baryshnikov was at the height of his fame that I could show just how much our appreciation of art in all its forms has declined.

To do that, I had to read and think a lot about the idea of “highbrow,” a term that makes me cringe almost as much as it makes me long for a time when there were at least some dividing lines between how we looked at and appreciated art. This breakdown of the idea of highbrow ended up getting cut from the final draft, but I think it presents an interesting look at the evolution and death of the idea over the last century or so.

The term “highbrow” has always carried with it a whiff of classicism. The term itself connects back to the pseudoscience of phrenology and the notion that people with higher foreheads have bigger brains and are therefore smarter than everybody else, and entered the lexicon in the early-20th century. One 1906 San Francisco Examiner society gossip column on the class divide at Vassar College at the time, described “Highbrows” as coming from Massachusetts, “and the littlest of the pretty Freshman Lowbrows from the Mississippi River Valley.” A 1907 item in The Emporia Gazette mentioned a successful run of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Cleopatra “will catch the highbrows who bring their books and nod at familiar passages.” In 1908, the Fall River Globe reported on Republican “Highbrows” spending lavishly to win elections all over the state. By the middle of the century, low- and middlebrow were also introduced into the lexicon. Russell Lynes, an editor at Harper’s, wrote in 1949 that class structure was on the way out; “It isn’t wealth or family that makes prestige these days. It’s high thinking.” He believed that the social structure America was headed towards was one where highbrows sat at the top, “middlebrow are the bourgeoise, and the lowbrows are hoi polloi.”

Since then, the various forms of “brow” have been tackled by widely. In 1960, Dwight MacDonald, who believed that for two centuries, “High” Western culture “that is chronicled in text books,” and Mass Culture that “really isn’t culture at all,” introduced his idea of Midcult, a “bastard” middle culture that “pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact waters them down and vulgarizes them.” There have been others. In 1992, Tad Friend, writing for the New Republic, lobbied “The Case for Middlebrow," and by the 2000s, we moved from “brow” to “Poptimism,” which was “a pure product of the zeitgeist,” as the writer Jody Rosen put it. Initially, it was coined to describe a certain strain of music criticism, but today, just about everything feels drenched in [forced] optimism.

The first music I recall being introduced to as a child was what we call “classical,” even though I’ve since learned that’s sort of a catchall term that almost usually means anything that’s complex, composed, devoid of lyrics (unless it’s opera), and almost always European or pre-20th century. When you just scratch away even a little bit, you start to learn it’s far more complex, that “classical” could include music by Philip Glass, the rags of Scott Joplin, or the avant-garde racket of Glenn Branca. The Rest Is Noise by Alex Ross does a great job at breaking down a lot of our cultural notions that what we consider “classical” is this precious music only made by and for rich white people. You’re reminded that Igor Stravinsky introducing The Rite of Spring in 1913 was the punk of its day—which is exactly the opposite of how I was taught to think about his music and anything else played on the classical station that was almost always on in the background.

My parents weren’t some sort of high culture snobs; they were as far from it as you can get, but my immigrant father had this idea that the best road for a baby born in America was to make sure they were "a genius” (his words) who could get into the best college and then get the best job. It didn’t matter what school or what career, so long as it was “the best” and they made a lot of money doing it, then that was what was important. There’s been a belief for some time that playing a child Mozart or Bach is a tool to make them smarter, and maybe it worked on me, but me learning to love or appreciate the music was seen as a means to an end. I did that on my own.

I still loved listening to the classical station as a teen and had grown obsessed with the jazz albums I could listen to at my public library as well. But by around 16, as my main interest had drifted towards louder and faster sounds, I’d made a stand that the one sort of music I hated was the pop that came out of the speakers. This was 1995, ‘96, etc. I was a punk long after the music and movement had supposedly died, and a few years after it allegedly “broke” again. But my snobbery was challenged when I learned about Ciccone Youth.

In 1986, members of the band Sonic Youth debuted a side project with members of the Minutemen and Dinosaur Jr. The whole thing was recorded as sort of a tribute to Madonna, who was one of the biggest pop stars in the world at the time when I was given a tape of the songs a decade later. The older kid who had dubbed it for me was trying to make a point that here was the band that basically everybody I knew considered the height of cool and indie rock (even though by that time, Sonic Youth was on a major label), and they were paying tribute to Madonna, not mocking her. Then there was the matter of Sonic Youth as a band who sounded and took as much influence from the avant-garde as they did punk, who were embraced by art gallery owners the same way they were beloved by Gen. X slackers. The more I thought about that, the clearer my understanding became that all the labels are just silly, but they also provide an opportunity to remake and rethink. By the end of the 20th century, when I started finding myself drawn to bands like Rachel’s, Explosions in the Sky or Godspeed You! Black Emperor, who were on indie labels or played punk venues and used elements of “classical” to create music writers dubbed “post-rock,” things had come full-circle for me. I’d melted down any terms used to categorize music, and everything just flowed into the same messy, noisy, beautiful pool. I could go from My Bloody Valentine to Steve Reich to Sunn O))) in just a single sitting and it was totally normal.

I mention all of this because I also got to talk to another one of my heroes for the Baryshnikov article, Laurie Anderson. Anderson is an artist who people have e tried to understand and categorize for decades, but it’s an impossible task to nail down what she does because she’s always shifting and moving as an artist. She and Baryshnikov have known each other for some time, but Anderson herself admits to not being that big of a ballet fan, but she appreciates that Baryshnikov is always challenging himself and playing around with each new project he takes on. But the thing that I keep thinking about is her line about how “There are a hundred times more artists now,” and “Everybody is screaming for attention, it’s incredibly corporate and it’s really speedy.” I’ve been chewing on that more than almost anything since I wrote the first draft of the piece, and the answer I came back to is that it all ties back to the initial idea of the profile. The various “brows” in art don’t carry the same weight as they once did. And while somebody like me who has this need that borders on sickness to always read and listen and watch and taste things, it was good to erase those lines between high, middle, and low art just as it was important that I learned classical music can mean so many things and nothing at all at the same time. But as art in America continues to come under attack, as funding is stripped away, books are banned, and corporate influence becomes even stronger, I can’t stop thinking whether the old ways of think were better, that at least we once thought enough about art ad its importance to elevate some of it to a higher level.

I pretty much live for the moments when I learn that another writer I like also listens to My Bloody Valentine.

I really appreciated this piece—thanks for this! I, too, had an immigrant dad who force-fed me classical music, hoping it might elevate me somehow. I also agree wholeheartedly that the concept of highbrow (and "brows" in general) is essentially a white classist construct.