Quick thing before I start this week’s newsletter. Two books I’m involved in are up for pre-sale right now. The first is Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan. I was honored to write the foreword for it and I think it’s going to be one of the (maybe the…) best books on Nora’s work you’ll read. The other is The Old Jewish Men's Guide to Eating, Sleeping, and Futzing Around. I can’t remember what I wrote about for it, but I’m sure it will cover gold chains, power donuts, James Caan, pickles, and other important topics. Pre-orders are vital, like truly important to the books having any chance at success upon release, and both of these books are things that I tend to talk or write about a lot, so smash that button and get them now.

I was talking with a chef friend a few months ago about trying to keep up with contemporary tastes while, as he put it, “Getting too crazy.” I had an idea what he meant by that, but before I could ask him to clarify, a pained look came over his face. He started talking about how a few years ago, in the years leading up to the pandemic, he’d sometimes go home at night after 16 or 17 hours in the kitchen feeling like a doctor who had to listen to people talk like they believed that they understood the world of medicine because they watched at least three seasons of Grey’s Anatomy and had a toolbar shortcut to WebMD on their browser. Customers, he said, had become too educated when it came to food. They thought they knew nearly everything because they read Eater or watched Bourdain, and what they didn’t know they asked with a dilatant's inflection: “Where did this chicken I’m enjoying live before this?” or “Did you go to go to Naples before you started making the city’s pizza? You know you need a certificate to make this, right?” Those sorts of questions used to annoy my chef friend, but he told me he often finds himself missing the shop talk with the people who were enjoying his work. “Nobody cares about food anymore,” he said. “Now they just want to take pictures and tell TikTok they checked out the place a million other people on TikTok said they checked out.”

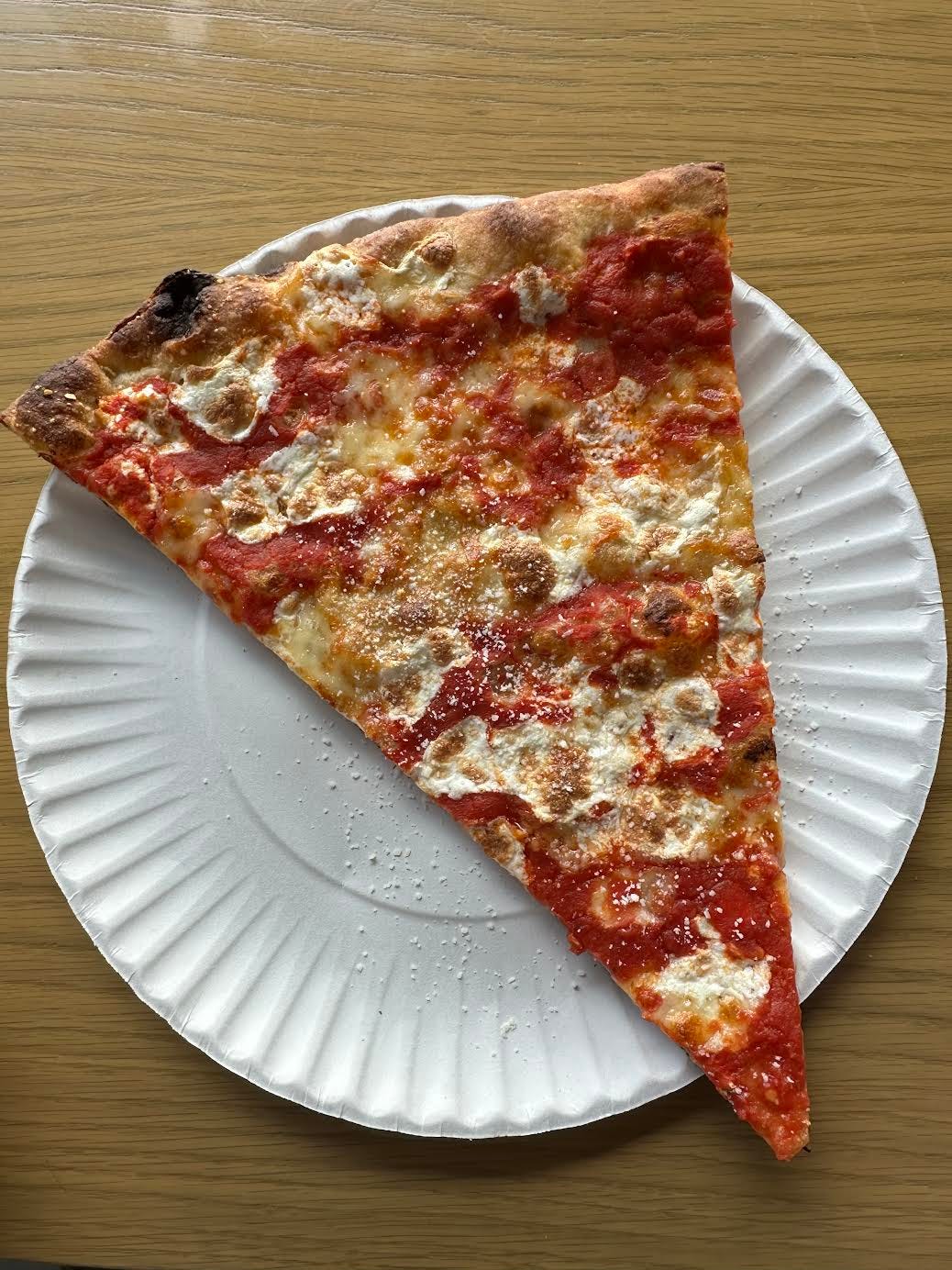

I thought about that conversation as I ate my plain slice at Fini Pizza Barclay’s Center location last week. The third Fini’s opened last fall, and the big story about Fini was that it was opened by Sean Feeney, co-founder of beloved Italian spots Lilia and Misi. Unlike Missy Robbins, his partner in those ventures, Feeny didn’t originally come from the food world; he came from the investment management firm Anchorage Capital Group. Feeney might or might not be able to cook you a decent meal, but he knows a good investment when he sees one, and backing Robbins was a wise move. Her restaurants are always packed and usually impossible to get into, which leads me to imagine Feeney is one of the rare cases of a NYC restaurant investor actually seeing returns on the money they put in. He picked a winner, so it doesn’t seem farfetched that he’d want to do some winning himself and open a place of his own.

And that’s where the problem comes in. A restaurant is a business like any other; they’re supposed to make money, but that's a Herculean undertaking in a big city like New York. You can’t blame a person for wanting to make a living, but as I munched on the plain slice I ordered from Fini and looked out at the Barclays Center plaza from the window seat, staring at the neon “You Belong Here” sign that went up not long after the city and NYPD made Black Lives Matter feel the exact opposite of belonging, I felt uncomfortable. Forget that the Fini I visited is in one of the most prime pieces of real estate in the city, housed in a space that a Starbucks couldn’t work in previously, just feet away from one of the busiest subway stops in Brooklyn. Even subtract that the other two locations are in Williamsburg and Amagansett. You can even overlook the decor, the sterile chic that you get when you walk into too many spaces these days; the basketball hoop surrounded by the green Fini X Local Hoops balls you can purchase for 60 dollars, and the piece of scotch tape asking customers not to “hoop” right underneath it. Everything is branded with the design work done by Polonsky & Friends, a firm whose aesthetic is hard to miss these days thanks to their work with restaurants and companies from the sexual harassment resource poster they designed for Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group that “pulls inspiration and mood from the 1960s french social revolution posters,” and the interior design concept for a Sweetgreen in Houston. On the “About” section of the Fini website, which exists as a button on the front page that reads “It was all a dream” button, the inspiration is said to be “a life long obsession of neighborhood pizzerias,” but there’s absolutely nothing neighborhoody about the place. Like countless other businesses that have popped up in Brooklyn over the years, Fini uses a Biggie quote to tell their story. Yet I’d imagine if a young Christopher Wallace stood in the space between Fini and the “You Belong Here” sign trying to make money the way he used to when he was just trying to feed his daughter, the cops would be on the scene within minutes. I’d almost be able to look past the location, Biggie appropriation, and feeling of sameness if not for the greatest sin of all: the pizza, like everything else at the Fini location, has absolutely zero soul. The sauce has this unnatural tang to it, there’s a deadness to the cheese that made me think it had been sitting around too long, and the custom-milled spelt flour used for the dough mixing with the tomato gives each bite a sweet-and-sour taste, but not sweet and sour in a good way. All that for five bucks. A triangle of sadness lacking any neshama.

Fini Pizza is another example of the no-soul movement becoming all too noticeable these days. It’s places and products that are obvious cash grabs trying to coast off the last fumes of the millennial marketing fever dream that sells everything from fast fashion at Target to fossil fuels as chill and empowering. Fini Pizza, with its locations in a basketball stadium and two more in some of the priciest parts of the tri-state area isn’t a “neighborhood pizza spot,” just like the glut of “foodtech” Blank Street coffee shops popping up like weeds don’t want to be the new local third place. All of these places and the people behind them just want to make money, and that would be totally reasonable if they didn’t try to sell what they’re doing as anything but a potential empire. and not some cool little part of the larger community I see it in the bagel shop down the block from me, Grabstein's. A few locations are scattered around the city, each one as sub-Russ & Daughters-looking as the next, with subway tile on the walls and “Protect your bagel put lox on them” signs out front. The place is sold as authentic and old-school, and there was once a Grabstein’s Delicatessen in Canarsie that closed in 1999, but this place just has the name. No person named Grabstein is involved as far as I can tell. The owners are Alan Philips, Jiansong Chen and Pongshing Chiu, and whether or not the place even makes their own bagels or has them brought in every morning, the counter person I asked couldn’t tell me while they were outside on their long vape break.

In some ways, it’s refreshing to see food business owners show that it’s all about the money in the end. David Chang spent years balancing being a great chef and public curmudgeon, but also a guy who (correctly) talked frequently about how important it is to honor the cultures that give us the sorts of food we love, whether it’s Mexican, Indian, or various types of Asian cuisines, like the Korean food Chang grew up with as a child of immigrants. How did he end up paying back those cultures in the long run? By sending cease-and-desist letters to anybody who tried to sell “chili crunch,” a Chinese condiment that has become popular in America over the last few years. I mention Chang with the Finis and Blank Streets of the world because while he has been one of my favorite big-name chefs whose restaurants I’ve loved over the years, the chili crunch thing (which he’s since apologized for) feels like a good indication of the larger no soul food movement. Chang himself seems more interested in growth these days rather than owning a few hot restaurants in NYC. He wants to expand and, frankly, the guy has earned it. But a lot of great chefs have gone down a similar road, using their name and power in the industry to coast, going from Michelin stars to getting their signature items sold in the frozen food section of every grocery store in America. And who can blame any chef for wanting that after spending an ungodly amount of hours working and hustling, putting up with the bullshit, the burns, the critics, and all the headaches that come with working in the industry? Cash in! Make your money. Just don’t do it at the expense of the people and communities you claim to care about.

Like it or not, this is capitalism, my friends. The thing that worries me about what all these examples represent is a move backward. It’s like my chef friend pointed out, that we went from caring too much, to not giving a damn. We should give a damn, especially when it comes to food. We should care about what goes into the coffee we drink or the places we choose to support. These things matter. We should want the things we eat and drink to have soul. When we start to forget that, we begin losing something deep and vital.

Not to be all “I just got back from my semester abroad”, but I was in Italy last week and it was refreshing just how... uncool every restaurant was. As in, no cutesy branding, no neon signs declaring “Pasta Slut” or something, zero interactions with a screen of any kind (and it goes without saying, but not even the barest hint that QR codes exist). Make restaurants boring again.

A Blank Street just opened in my Boston neighborhood and I’ve been unable to explain my uneasiness with the shop. No soul…spot on.