You likely read the news last month that Pitchfork is being “folded” into GQ. I write for the latter and I still don’t know exactly what that means except that there will be less Pitchfork, which means there will be one less outlet to read music criticism that actually goes through an editorial process and could have some wider impact on the way the public consumes an artform. You can still read people writing smart things about bands you’re curious about at places like Stereogum or The Quietus, but the places you can go to and read smart takes and reviews that you might not always agree with (that’s sort of the point…) are dwindling. And that’s not a good thing. In fact, it’s very bad.

We need criticism. The problem, I find, isn’t so much the excuse that “Nobody reads it” or “It isn’t profitable,” it’s that a lot of people see the word “critic” and they think that person’s only intended purpose in this life is to criticize. Many people don’t understand what it means to be critical, and that is a big problem.

When the Pitchfork news broke, there were the countless takes we’ve all come to expect. Plenty of them used some variation on the “death of criticism” argument that has been around in one form or another for as long as I can recall, while some seemed to take enjoyment in seeing Pitchfork get turned into…whatever. I didn’t always love everything I read on Pitchfork, but I often got something valuable out of it, whether it was learning about some new artist or scene or looking at a classic record a different way when they began rolling out the Sunday Reviews series. But one tweet in particular really pinched my ass. I won’t link or post it because plenty of people already chimed in to tell the person they were wrong, but it read “The death of music journalism is kinda odd to me but also makes sense as a byproduct of streaming platforms; wider access to music means people don’t need to rely on critics, gatekeepers as much to pre-vet for them what’s good and what isn’t.”

That, by a person I have to assume is on the younger side since they mention being a writing fellow in their bio, is exactly the sort of take that breaks my heart. We shouldn’t rely on anybody to pre-vet anything for us. If you sit around and wait for a person or a couple of people to tell you if something is “Good” or “Bad,” you’re going to miss out on so much. And, again, that isn’t the critic’s primary focus. As fun or anger-inducing as something like the Pitchfork rating or the Siskel & Ebert thumbs up or down could be, those things are carnival tricks. They get people talking. It’s easier to say “Well, this record got a 6.2 and I need it to be a 7.0 or higher if I’m going to listen” than it is to give thought to every line and point in a review. It’s easier to let somebody else have thoughts and opinions. It’s easy to let somebody else make decisions for us. Easier isn’t good. It’s dull. We let dull pap pass and we dull ourselves without criticism.

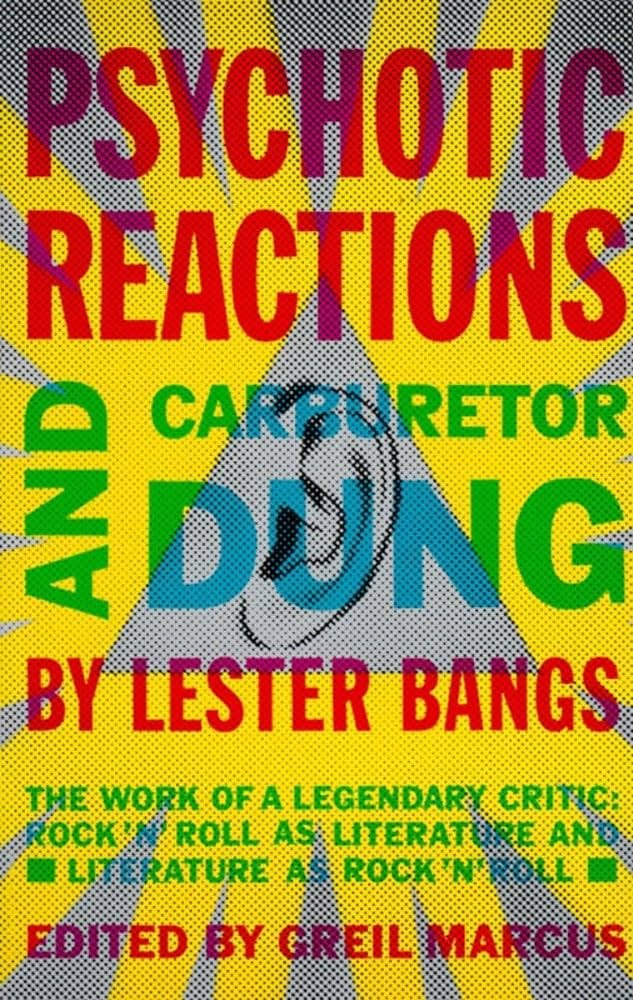

When I was about 15, I read Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic: Rock'N'Roll as Literature and Literature as Rock 'N'Roll by Lester Bangs. What I didn’t understand then was how many other people who had dreams of maybe someday writing also read it, and so many of the worst record reviews I’ve read (and maybe a few I wrote when I was younger) were influenced by Bangs. But that’s beside the point. Reading Bangs was the first time I really engaged with a person whose main focus was being a critic, and I think maybe my brain was still soft enough at this point that it soaked something in that stayed with me. And while I can’t say how much Bangs has influenced me since I was a teenager, a few years later, a mention of one of his reviews led to a big revelation. I said something about his Tangerine Dream concert review trying to impress somebody older and cooler than me, and they shook their head. They said Lester Bangs was “whatever” (this was 1998 or so) and that I should read Ellen Willis, she was better. I said OK, spent a good amount of time tracking down anything I could by her (thankfully, her stuff is easier to find), and had a huge “Oh shit” moment when I finally did.

Flash-forward a decade. I’ve read a lot more and I think I know some shit. I’ve gone through a good chunk of the books we’d consider “classics,” but I have this one blind spot that I can’t get past and it drives me nuts: Ulysses. What in the hell is the deal with this very big James Joyce book that people have been obsessed with since it came out? It seems to have had some Velvet Underground-type impact because everybody who read it and decided to become a writer. What’s the deal with Ulysses?

Then, one day, after my second attempt to get through a few pages, a friend who was obsessed with the book told me something that really started to change everything for me. “You don’t need to read Ulysses if you don’t want to. But you should read as much criticism on it as you can before you decide to give up.” I took him up on that and eventually found some piece out of an obscure journal from the late-1970s or so that looked at Ulysses and its impact on modern comedy, how you could go from Joyce’s doorstopper to the dialogue of the Marx brothers (especially the couple of films S.J. Perelman co-wrote) to the darkly comedic American literature of Thomas Pynchon. I don’t remember much else about the review, but those little comparisons switched something inside of me. I liked the Marx brothers and Pynchon! It made me want to give the so-called masterpiece another chance because...it was funny.

And it is! It’s a funny book. It might take a little head-tiling to get the humor, but the problem with Ulysses is that we label it a “classic,” and there’s still a prevailing mindset that “classics” need to be tragic and dramatic, and that comedy is somehow lesser (my friend Jesse David Fox does a great job countering this in his work of criticism, Comedy Book), so it’s not initially presented to readers as a book that’s as funny as it is groundbreaking and large. I never would have considered that until I read that one piece of criticism.

I have this theory that we should all take our reading diets as seriously as we might monitor the other things we put into our bodies. If we’re going to monitor what we eat or drink, it seems only right that we’d want to do the same with the things we feed our brains. There’s so much content out there, and so much of it is trash that it’s more important than ever to be vigilant about what we take in. The way I try to do that is by making sure I’m reading at least one poem, a little bit of fiction, news and commentary from sources I trust—even if I disagree with some of the writers or opinions, that is still important save for a few examples—and at least one piece of criticism every day. The criticism I’m reading could be current or it could be something Irving Howe wrote 50 years ago. It might be Teju Cole looking at photographs, or maybe it’s something about a film I’ve never seen being reviewed at Little White Lies. It could be in the back of the issue of Harper’s or maybe it’s one of these newsletters, the point is to keep engaging. I hope the publications that allow me to do that as a reader will always be around, and I suspect that sooner or later, there will be something by somebody that will be “Their” Pitchfork. Maybe I’ll read it, and maybe I won’t get it. But that doesn’t matter. I don’t matter in the grand scheme of things. What matters is that we learn to better appreciate and cultivate criticism because it serves as the conscience of all art and culture.

Agree that media diet is huge. A couple years ago, when I was trying to level up my own writing career, I decided to finally put down the money for a bunch of quality subscriptions: WSJ, FT, New Yorker, etc. Aside from the quality of the writing and reporting, it just exposed me to things my own dumb Instagram algorithm or websites comfortably in my own political persuasion weren’t. Just going off social media and free-to-read SEO factories is like having a bag of Taki Fuego every night for dinner.