Friends. Thanks for opening this. Quick update on the Diamond Book Club (better name pending) is that I’m getting set to announce the first title next week. The aim is a new title every other month, and there will be some sort of theme that ties together the titles I pick. It will be a mix of old and new titles with a few different components to the whole thing. More soon, but this will be subscribers-only, so sign up now and get in on that.

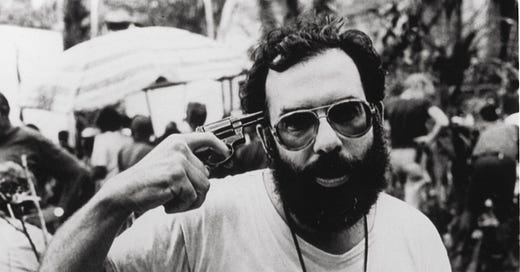

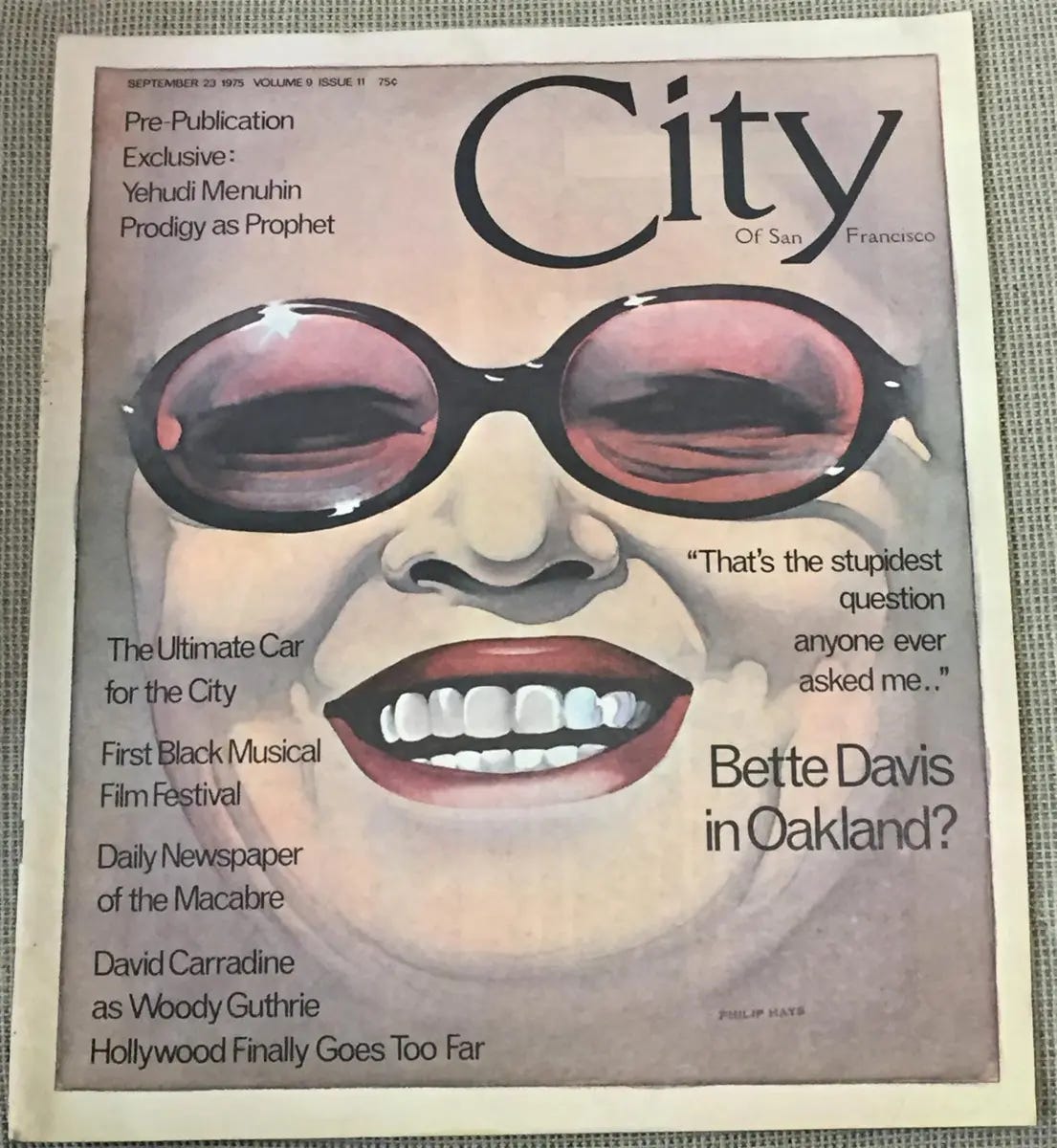

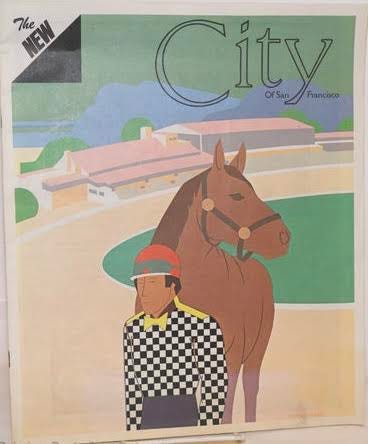

“Publishing is worse than the movie business—the egos, the feeling that you've stepped in somebody else's terrain” sounds like something that somebody getting out of the media industry in 2024 might say as we continue to see publication after publication after publication fold, lay off their staffs, or both. But it’s not from today, yesterday, last month, or last year; it was Francis Ford Coppola in 1975 talking about trying to run City magazine in San Francisco.

Coppola bought into the small magazine in 1973, but went all-in a year later, dropping over a million of his own dollars into it. That’s a Coppola specialty that we’re all currently seeing in action with him self-funding the making of Megalopolis with $120 million of his dollars. I’ve been thinking a lot about Coppola’s philosophy for buying artistic freedom lately after a line in Rachel Syme’s New Yorker profile of Sofia Coppola really stuck out to me where she mentions that her father, who has made more money selling his wine opening hotels, “taught us how to make money doing other things, so that you don’t have to count on the movies for that.” Coppola is willing to use his own money to make things happen. Sometimes it works—and then there was City.

Coppola had some pretty wild ideas for how to grow the business. One, as reported in an issue of Time in 1975, was "to hold the magazine's weekly closing in a theater and open the event to the public. Editors would do their work onstage, with galley proofs flashing on a screen behind them, and the audience offering comments, which would be published as a special page of the magazine.” There were also some perks for subscribers. A December 1974 article in the New York Times describes a chaotic scene leading up to the premiere of Coppola’s second Godfather movie:

Two weeks before the New York opening of ''The Godfather, Part II,'' Francis Ford Coppola is the calm center of a whirlwind of activity. A team of editors is working around the clock - right through Thanksgiving - in order to meet the deadline. At the first public showing of the movie, for the subscribers of San Francisco's City magazine (which Coppola owns), the projector breaks down four times.

He had a lot of other big plans, a few of them brought up by Stephen Schwartz in an article looking back on City:

Coppola began the enterprise by reviving the career of the Depression-era screenwriter John Fante, gushing over the opportunity to publish a Fante novel, “Brotherhood of the Grape.” And at the same time as he resuscitated Fante he called on all Bay Area writers to submit articles. The magazine was swamped with thousands of manuscripts. Many unfortunates believed that entry into City would lead to, say, a movie job[.]

I love an idea that, in retrospect, you can see was for sure going to fail. There were issues from one editor’s “free hand with Coppola’s money,” to Coppola being, well, Francis Ford Coppola. He’s a director. They tend to be obsessive and have been known to act a little, say, overbearing. The publication was done by 1976. Cathie Black, who went on to a successful career as president of Hearst and eventually a short, but, um, memorable run as New York City Schools Chancellor, wrote in her self-help book disguised as memoir (or is it the other way around?), Basic Black: The Essential Guide for Getting Ahead at Work, about getting a job in ad sales at City. She uses the experience of getting the gig to teach a life lesson. He marriage was ending and she wanted a change of scenery when she heard about Coppola’s new venture. She asked her old boss if he could make an introduction. He said sure.

As it turned out, Coppola was in New York that day, and within a few hours I was on my way to meet with him at a large suite in the elegant Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue. A couple of days later I had an actual job offer. The truth is, if I’d relied only on myself, I’d probably have never gotten through his gatekeepers to set up that initial meeting.

But things didn’t last long. Black later recounts that after coming home from a ski trip, she learned “the magazine had been shut down, with only a note posted at the entrance telling employees that the last issue had been printed, and they didn’t have jobs anymore.” But at least she learned something from the experience: “So don’t be shy about using your contacts. Most people are flattered when you ask for help.”

People tend to have different views of Coppola’s City, but I find that most of its history has been written by people whose careers were affected by it at the time, many of whom went on and did bigger things. Coppola wasn’t totally turned off by the magazine business; he would go on to create Zoetrope: All Story in 1997, and it continues to be a great read to this day. Yet I can’t help but think about how in 50 years since Coppola named himself publisher of his quixotic publication, how many other various magazines, newspapers, and websites have come and gone, but also how the most interesting ones always involved some sort of risk-taking and trying something different. Most of them eventually failed, but when you look back at what came after those publications, that’s when you start to see some of the more interesting results. It could be Graydon Carter going from Spy to the Observer to Vanity Fair in the 1980s and then ‘90s, and all the ways that shifted the media landscape in countless ways. Or it could be something like ex-Deadspin staffers doing their own thing with Defector and helping show a new way to run a publication without corporate oversight mishegos in the way. That’s my hopeful stance on what’s been going on in recent times with all the news of media turmoil, that all this shit will eventually help grow flowers.

"Editors would do their work onstage, with galley proofs flashing on a screen behind them, and the audience offering comments, which would be published as a special page of the magazine.”

I can't believe this didn't work. :)